I am honoured to be on the ancestral lands of the Whadjuk Noongar people and I acknowledge the First Australians as the traditional custodians of this continent whose cultures are among the oldest living cultures in human history. I pay respect to the Elders of the community and extend my recognition to their descendants who are present.

NON-ESSENTIALISM & ESSENTIALISM

Non-essentialism states that culture isn’t a locale that someone belongs to. It isn’t something real or solid, rather it’s an ever changing and morphing social force (Holliday, Kulllman, & Hyde, 2017). Non-essentialism sees that people negotiate culture rather than being governed by it and recognises that people can move through a variety of cultures in a dynamic, as opposed to static, way. It rejects the idea that cultures have a set of indicators that are unique to one society alone. As mentioned by Holliday et al. (2017) society has complex characteristics that are challenging to identify, but non-essentialism has the ability to gain a deeper understanding of culture through social behaviour.

Essentialism is a simplistic and narrowminded way of assigning groups to people and places, and it claims homogeneity. It can be seen as “the attribution of certain characteristics to everyone subsumed within a particular category” (Phillips, 2010, pg. 47). It is used for various socio-political purposes at different times. Stereotyping and prejudice are common by-products of essentialism, attempting to define and confine people, especially through media. The recent Covid-19 pandemic has brought essentialism to Chinese and Asian people, much like Ebola did to West African people in 2014. The Australian flag is another example of a direct link to our dark Colonial history and does not represent all Australian’s. It does not in any way recognise our Indigenous custodians and may trigger trauma.

OTHERING

Othering can be explained as “imagining someone as alien and different to ‘us’ in such a way that ‘they’ are excluded from ‘our’ ‘normal’, ‘superior’ and ‘civilised’ group” (Holliday et al., 2017, p. 2). Over-generalising is used to silence minorities and groups classed as different to ourselves by reducing others to less than they are Holliday et al. (2017). It insinuates a hierarchy and, in their diminishing, my group becomes elevated. Furthermore, easily digestible assumptions inhibit “negotiation of identity between people” (Holliday et al., 2017, p. 263) and stops real connection. We see this often in Western culture where “being ‘foreign’ or ‘different’ to “Western eyes” stems from essentialist modes of thinking, talking and portraying cultural differences as unfamiliar, strange and unusual (Mohanty, 1988, as cited in Samie & Sehlikoglu, 2015). An example of Othering is the treachery that occurred in the disgraceful case of Gregory Andrews and the forced removal of children in the NT. It is a clear example of the media circulating an ideology, and the dominant group enforcing power through law, the justice system and the police that protect that ideology. Destructive Othering from our elected leaders and representatives can become commonplace thinking where atrocities like this are allowed to happen.

My area of study is Fine Art and Visual Culture, with a keen interest in Indigenous art. A walk through most major Australian art galleries will show a trove of colonial art and little representation of Australia’s Indigenous artists. The denial of Indigenous Australians’ art history has ostracized and excluded them from everyday Australian life. Othering can also be seen in the underrepresentation of women, yet some progress is being made. Weston (2017) notes that galleries like MOMA are addressing the imbalance of gender by expanding their acquisitions to include more women artists. Problems also exist with exploiting minority groups. In an artist’s attempt to shape their own identity through language about their work, art critics may impose a dominant discourse that marginalises them (Holliday et al., 2017). Taking this into my future career will be an important aspect to lessen the divide and nurture a platform for expression, whatever that may look like.

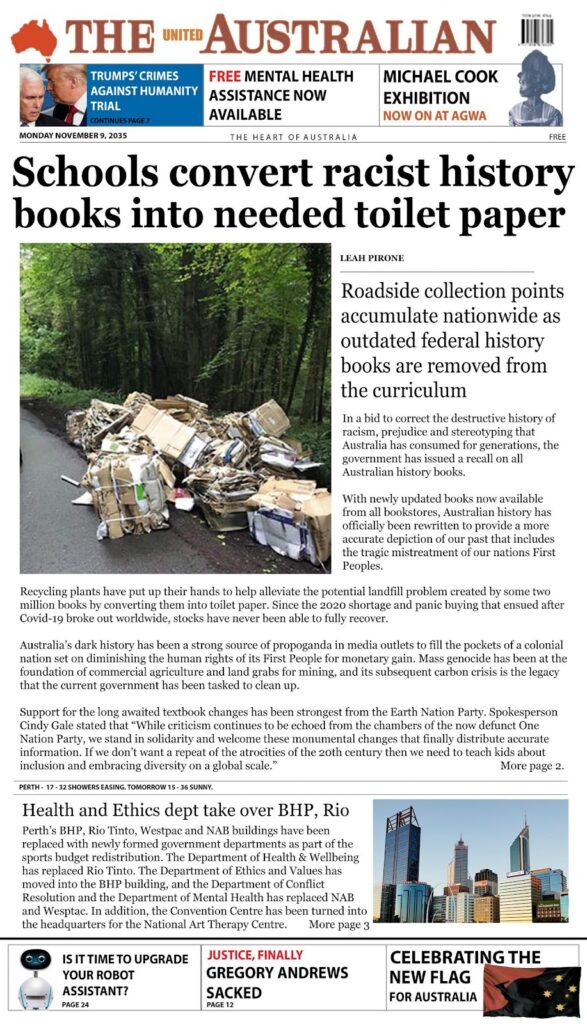

Media plays an enormous role in public opinion, and typecasting others and racism are two areas that I visit often through graphic design and other mediums to evoke reflection and reshape views. In the newspaper below, the year is 2035, fifteen years from now. The encoding and values within the artwork is that of inclusion, representing a non-essentialist society attempting to re-educate, reinform and reform. The main article is not claiming it has predefined or set boundaries for what a new Australia might look like, rather it is navigating new ground. If culture is indeed “something that flows and shifts between us, it both binds us and separates us, but in different ways at different times and in different circumstances” (Holliday et al., 2017, p. 72), then media like this is integral in creating a culture that embraces diversity.

Although my newspaper began with good intentions it unintentionally detours into essentialist territory because I have made assumptions that all readers would find the humanities beneficial, but that may not appeal to others as much as it appeals to me. Holliday (2016) states that in our attempts to make sense of and construct culture we often engage in both essentialist and non-essentialist views at the same time, as I have done here. In reality, views move between both essentialism and non-essentialism.

I believe this artwork has been successful in showing that the reductionism of the past can be changed with leadership that is not afraid to speak out against discrimination and make necessary changes. Essentialism must be challenged wherever it appears, or we will remain stuck and repeat history ad infinitum.

REFERENCES

Holliday, A., Kulllman, J., & Hyde, M. (2017). Intercultural Communication: An advanced resource book for students (3rd ed.). Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

Holliday, A. (2016). Difference and awareness in cultural travel: Negotiating blocks and threads. Language and Intercultural Communication, 16 (3), 318-331. https://doi-org.dbgw.lis.curtin.edu.au/10.1080/14708477.2016.1168046

Samie, S.F., & Sehlikoglu, S. (2015). Strange, Incompetent and Out-Of-Place. Feminist Media Studies, 15(3), 363-381. https://doi-org.dbgw.lis.curtin.edu.au/10.1080/14680777.2014.947522

Phillips, A. (2010). What’s wrong with Essentialism? Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory, 11(1), 47-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2010.9672755

Weston, G. (2017). Gender equality in the museum: The Cruthers collection of women’s art. Artlink, 37(4), 62-69. https://search-informit-com-au.dbgw.lis.curtin.edu.au/documentSummary;dn=268996964090096;res=IELHSS

© 2021 Leah Pirone All Rights Reserved